Advertisement

Cryptocurrencies have become an obsession for environmental lovers because of the huge amount of electricity it consumes for the network, but one part of the industry insists that it can solve another angle of the climate crisis: Carbon crypto credit.

In the coming years, companies like Procter & Gamble (PG) and Nestle (NSRGY) promise that they will “carbon neutralize,” meaning that when carbon is released, they will also prevent carbon from entering the atmosphere elsewhere.

One of the ways in which these companies achieve their emissions targets is by buying carbon credits — the kind of certification for an amount of CO2 that has been removed from the air by conservation actions or cuts.

While many see carbon credits as a practical solution to the global climate crisis, others argue that they only make matters worse – giving polluters the right to be released more than they can.

However, many cryptocurrency projects are supporting carbon credits. Projects such as Toucan, Regen, and Moss say that “on-chain” carbon credits will increase transparency and improve access to the carbon credit market.

From most veterans of the carbon industry and environmental scientists to retail investors and accountants have all been involved in the renewable finance movement of cryptocurrencies, also known as ReFi.

Regenerative Finance is the priority of the flow of investment capital to areas that have an impact on the community such as race, the economy, and the environment; rather than investing in areas that have a negative impact on the community.

But everyone has a different view of how and to what extent to leverage cryptocurrencies to solve the crisis of this era.

The relationship between cryptocurrencies and the environment

Today, it’s hard to find any articles about cryptocurrencies and the environment without mentioning the huge amounts of energy consumed by the two largest blockchain platforms, Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Both networks use a Proof-of-work consensus mechanism that consumes energy. In it, a large number of computers around the world compete with each other to process transactions, an activity known as “cryptocurrency mining”.

According to the Cambridge Bitcoin Power Consumption Index (CBECI), cryptocurrency mining consumes 135 TWh of electricity per year – more than Norway consumes in a year. According to CBECI estimates, Bitcoin – commonly referred to as “crypto gold” – consumes more energy than real-world gold mining.

However, many in the industry say that this comparison is incorrect – especially when considering the volume of energy used to mine money that comes from renewables.

Moreover, not all blockchain platforms require the same energy. In addition to Bitcoin and Ethereum, most other blockchain platforms use a more sustainable Proof-Of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism. Ethereum is in the process of transitioning to PoW, which they assume will cut energy consumption by about 99.95%.

But no matter what the carbon footprint of cryptocurrencies is, it will take some time for the public to stop seeing blockchain technology as a threat to the environment.

Meanwhile, the ReFi movement is bringing a new, more environmentally friendly aspect to cryptocurrencies.

What is a carbon credit?

ReFi’s proposals for tackling the climate crisis are primarily focused on reforming the global carbon credit market.

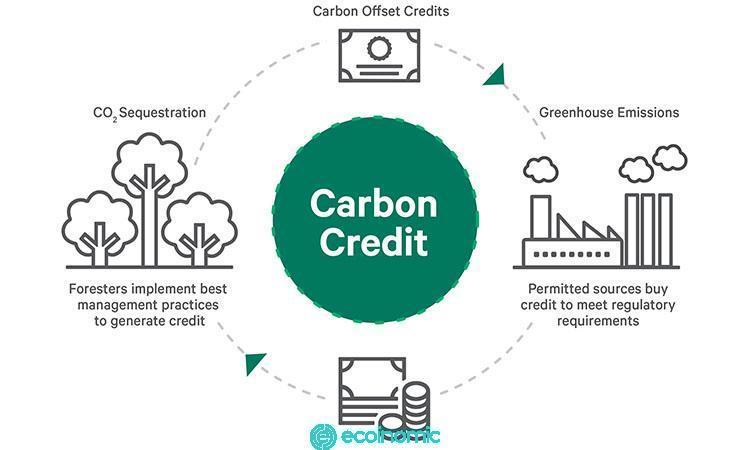

Carbon credits – also known as carbon compensation – represent projects that reduce emissions or remove CO2 from the atmosphere, such as preserving forests, building wind farms and solar power, or capturing methane.

In general, a carbon credit denoting 1 ton of CO2 is removed from the environment. For buyers, it denotes permission to release an equal amount of carbon into the environment without conviction (and sometimes tax-free).

The global carbon market emerged in 1997 with the Kyoto Decree, an international treaty that generates carbon credits as a way for countries to compensate for their emissions. This is the regulation set out by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Since then, many international organizations have begun implementing and selling carbon credits. In recent years, a “volunteer” carbon market has emerged to allow environmentally conscious companies — including many cryptocurrency miners — to compensate for their emissions more than the government regulates.

Challenges with carbon statistics

Carbon statistics skeptics point to research showing that many carbon credits are not as clean to the environment as it represents. Many cases are documented of fraud, double counting, and creative accounting, which produces large amounts of unreliable carbon credits.

Accurately measuring how much CO2 is removed from the environment is extremely difficult. And shoddy credits can harm the environment by allowing companies to superficially offset their emissions while emitting more than they originally did.

Many companies are willing to buy cheap credits from questionable conservation projects in exchange for a good public relations image. This means that volunteer credit sellers are less motivated than the sellers required to carry out the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) activities correctly.

A more transparent carbon market

The recommendation for carbon “on-chain” is simple: integrate the voluntary carbon market into the blockchain and attach each credit to metadata. These data will verify their quality and origin publicly. Those who want to compensate for their emissions will have access to a transparent and liquid carbon market.

When it launched in October 2021, Toucan generated a wave of controversy over its partnership with KlimaDAO, a new blockchain platform built and managed by a community of unnamed KLIMA token holders.

With Klima’s help, Toucan has integrated 20 million tons of carbon onto Ethereum’s Polygon sidechain, turning 5% of all credits on Verra, the largest voluntary credit registrar, into tokens.

The integration of credit with the Toucan Blockchain means invalidating that credit in its original registry to avoid being charged twice. After that, Toucan will issue an NFT representing this credit.

But one challenge for the carbon market is that credits from different projects are not interchangeable. In other words, there are many project groups that are said to be more effective than other projects in removing carbon from the environment. So the price of these credits also varies.

Even with an open blockchain market, Toucan’s TCO2 tokens are hard to exchange because each token represents a specific project. Without a large amount of other TCO2 on the market, it is difficult for people to buy and sell specific types of credits. In the language of the market, TCO2 – or carbon credits in general – is lacking in liquidity.

But even if Toucan uses DeFi’s “liquidity tank” to create the infrastructure for the carbon market, it doesn’t make sense if Toucan can’t convince people to deliver carbon credits into the tank. This is a difficult proposition as most institutions, including Verra, are unwilling to recognize the legitimacy of credit integrated by Toucan because they are essentially no longer valid when added to the “on-chain”.

That’s when Toucan needed KlimaDAO’s help to provide liquidity to the platform. KlimaDAO’s “Carbon Black Hole” has gathered 40,000 “Klimates” to provide Toucan’s “on-chain” carbon ecosystem with the amount of CO2 it needs.

Not only does it provide liquidity to the cryptocurrency carbon market, Klima also establishes a fundamental principle in carbon statistics: the higher the price of carbon, the better for the environment.

For a while, Kilma’s strategy of raising carbon prices worked. In the first week, the price of KLIMA skyrocketed from less than $2,000 to over $3,000. Meanwhile, KlimaDAO also issued tons of KLIMA tokens to holders of their shares who locked their tokens in smart contracts that they couldn’t sell. At that point, holding shares in KLIMA could cause your balance to increase 300-fold within a year.

However, the project was quickly criticized as a Ponzi scheme. That is, if enough people decide to sell their KLIMA tokens, the feedback loop will quickly cause the price to go down in a spiral, resulting in an effect that everyone will eventually have to sell their tokens or take a risk when things get to zero.

And this has come true. In less than two months after Klima and other similar projects skyrocketed in price and created a craze in DeFi, the Ponzi scheme collapsed. The price of KLIMA used to be over $3,200, but now it’s only $20.

Valuable lessons learned

However, even if Klima doesn’t make a big increase in the price of carbon, it at least plays a role in boosting the fledgling cryptocurrency carbon ecosystem by helping it reach thousands of investors and provide the necessary liquidity.

At the very least, Klima’s experiment has demonstrated that if used creatively, the tools of cryptocurrencies can make a mark in the carbon trade.

But it must also be acknowledged that the blockchain carbon market is not an easy solution to the climate crisis problem.

Related: Polygon partners with ocean conservation NGO to advance ocean literacy